Grist

In the US, a fungal disease is spreading fast. A hotter climate could be to blame.

- Jul 29, 2023, 6:01 AM

Climate Connections is a collaboration between Grist and the Associated Press that explores how a changing climate is accelerating the spread of infectious diseases around the world, and how mitigation efforts demand a collective, global response. Read more here.

In 2016, hospitals in New York identified a rare and dangerous fungal infection never before found in the United States. Research laboratories quickly mobilized to review historical specimens and found the fungus, called Candida auris, had been present in the country since at least 2013.

In the years since the discovery, New York has become an epicenter for C. auris infections. Now, as the illness spreads across the U.S., a prominent theory for its sudden explosion has emerged: climate change.

As temperatures rise, fungi can develop tolerance for warmer environments — including the bodies of humans and other mammals, whose naturally high temperatures typically keep most fungal pathogens at bay. Over time, humans may lose resistance to these climate-adapting fungi and become more vulnerable to infections. Some researchers think this is what is happening with C. auris.

[Read next: A brain-swelling illness spread by ticks is on the rise in Europe]

When contracted, the fungus can cause bloodstream, wound, and respiratory infections, and other severe illnesses. Though not usually dangerous for healthy people, it can be an acute risk for older patients and others with preexisting medical conditions. The mortality rate has been estimated at 30 to 60 percent, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC, and it’s a particular risk in health care settings where infections can easily spread, such as hospitals and nursing homes.

The pathogen was first identified 14 years ago in Japan and then found to have emerged spontaneously in three countries on three continents: Venezuela, India, and South Africa. In the U.S., the most cases last year were found in Nevada and California, but the fungus was identified clinically in patients in 29 states. New York remains a major hotspot.

Fungal disease expert Arturo Casadevall, a microbiologist, immunologist, and professor at Johns Hopkins University, said that humans normally have tremendous protection against fungal infections because of our temperature. “However, if the world is getting warmer and the fungi begin to adapt to higher temperatures as well, some … are going to reach what I call the ‘temperature barrier,’” he said, referring to the threshold at which mammals’ warm body temperatures usually protect them from infection.

When C. auris was first spreading in the U.S., cases were linked to people who had traveled here from other places, said Meghan Marie Lyman, a medical epidemiologist for mycotic diseases at the CDC. Now, she said, most cases are acquired locally, generally spreading among patients in health care settings.

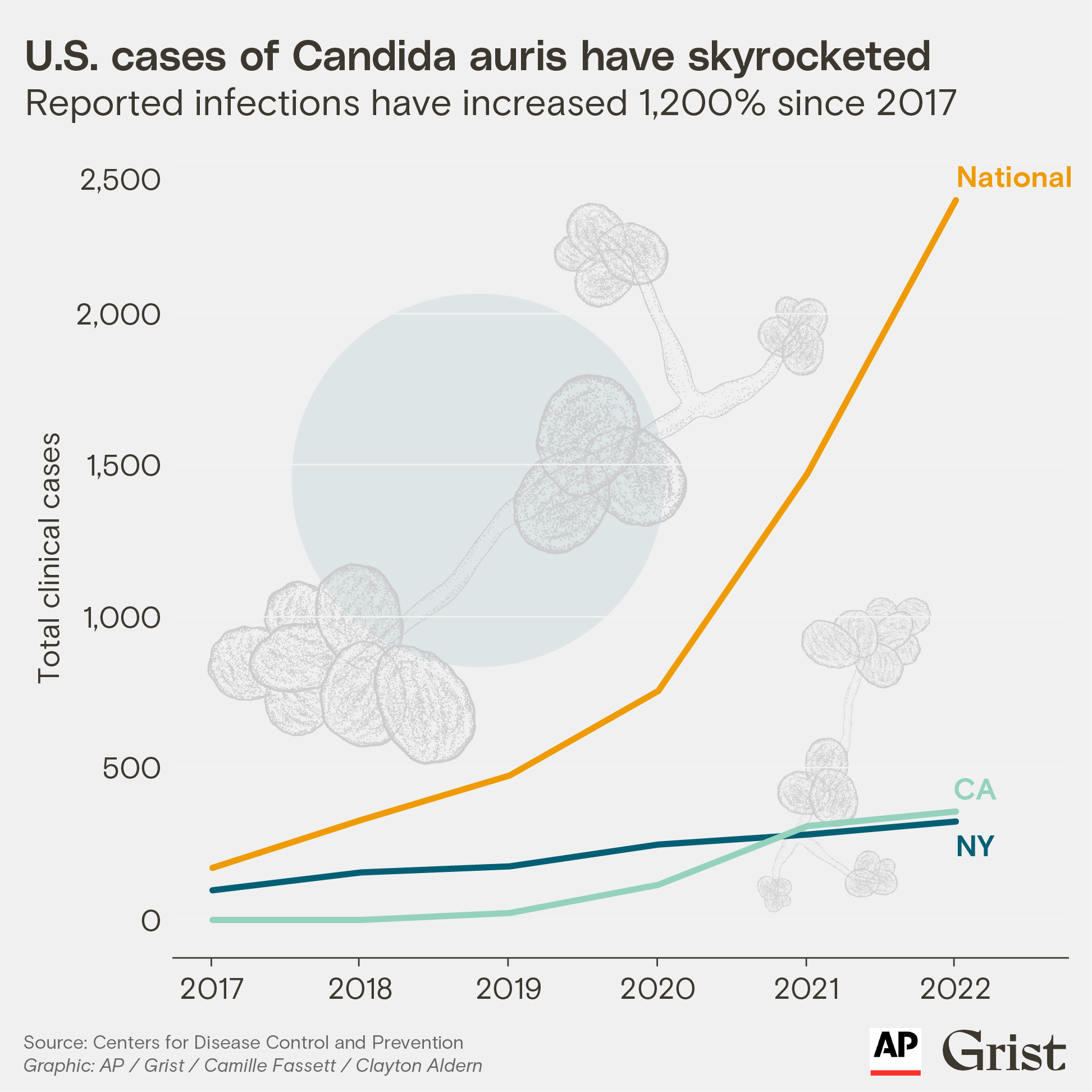

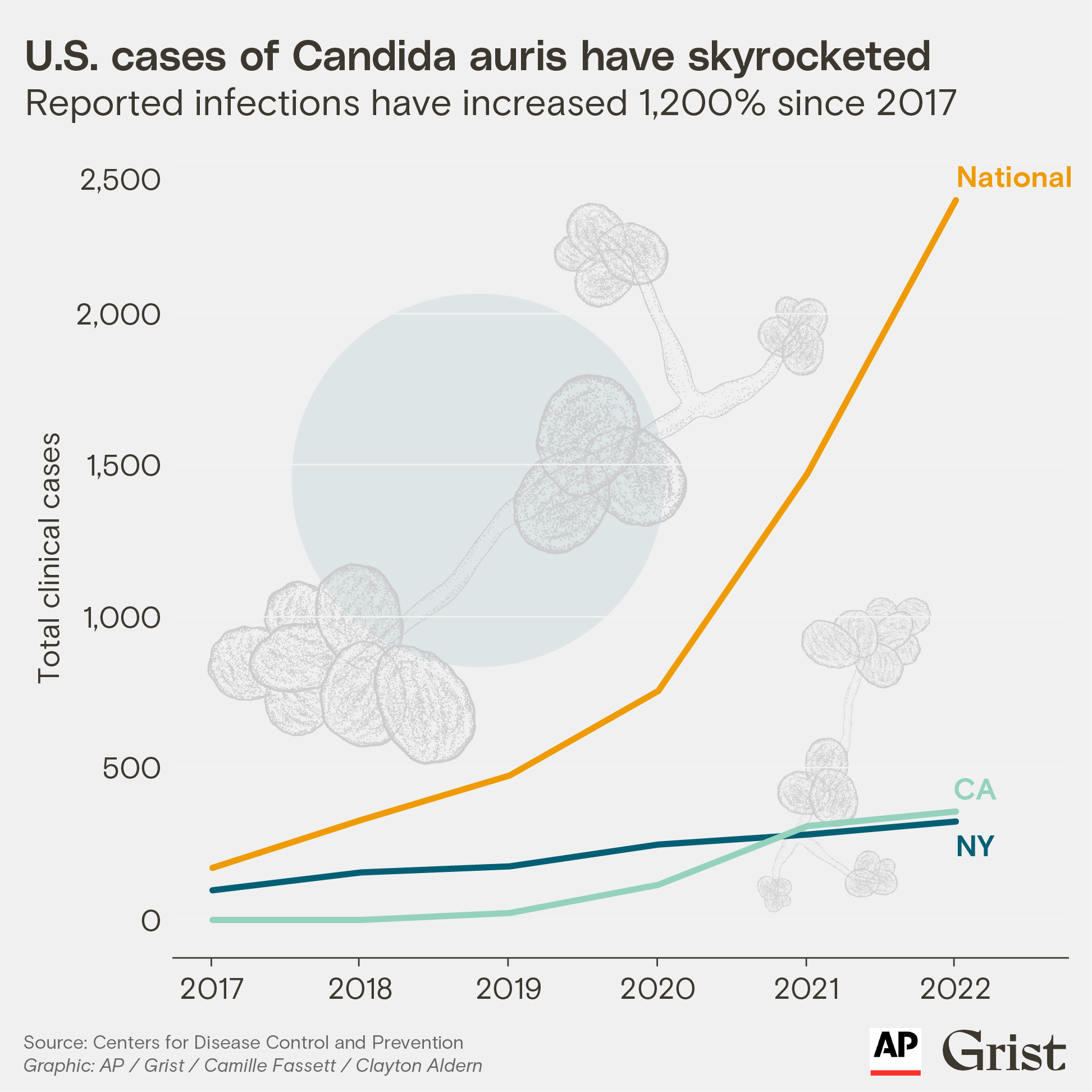

In the U.S., there were 2,377 confirmed clinical cases diagnosed last year — an increase of more than 1,200 percent since 2017. C. auris is also becoming a global problem. In Europe, a survey last year found case numbers nearly doubled from 2020 to 2021.

“The number of cases has increased, but also the geographic distribution has increased,” Lyman said. She noted the skyrocketing numbers represent a true increase in cases, not just a reflection of better screening and surveillance processes.

In March, a CDC news release noted the seriousness of the problem, citing the pathogen’s resistance to traditional antifungal treatments and the alarming rate of its spread. Public health agencies are focused primarily on strategies to mitigate transmission in hospitals and other health care settings.

“It’s kind of an active fire they’re trying to put out,” Lyman said.

Dr. Luis Ostrosky, a professor of infectious diseases at McGovern Medical School at UTHealth Houston, thinks C. auris is “kind of our nightmare scenario.”

“It’s a potentially multidrug-resistant pathogen with the ability to spread very efficiently in health care settings,” he said. “We’ve never had a pathogen like this in the fungal-infection area.”

As temperatures rise, fungi can develop tolerance for warmer environments — including the bodies of humans and other mammals.

C. auris is nearly always resistant to the most common class of antifungal medication. Occasionally, it can be resistant to the broadest spectrum antifungal.

“I’ve encountered cases where I’m sitting down with the family and telling them we have nothing that works for this infection your loved one has,” said Ostrosky, who has personally treated about 10 patients with the fungal infection but has consulted on many more. He says he has seen it spread through an entire ICU in two weeks.

As researchers, academics, and public health groups investigate theories that explain the emergence of C. auris, Ostrosky said that climate change is the most widely accepted one. Global temperatures rose about 2 degrees Fahrenheit between 1901 and 2020, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the global average temperature is expected to continue trending up in coming decades. Climate change has been found to make heat waves more likely, and a recent study found that temperatures crossing the103-degree mark — classified as “dangerous” heat by the National Weather Service — will be three to 10 times as common by 2100.

The CDC’s Lyman said it’s possible the fungus was always among the microorganisms that live in the human body, but because it wasn’t causing infection, no one investigated until it recently started causing health problems. She also said there are reports of the fungus in the natural environment — including soil and wetlands — but environmental sampling has been limited, and it’s unclear whether those discoveries are downstream effects from humans.

“There are also a lot of questions about there being increased contact with humans and intrusion of humans into nature, and there have been a lot of changes in the environment, and the use of fungi in agriculture,” she said. “These things may have allowed Candida auris to escape into a new environment or broaden its niche.”

Wherever and however it originated, the fungus poses a significant threat to human health, researchers say. Immunocompromised patients in hospitals are most at risk, but so are people in long-term care centers and nursing homes, which generally have less access to diagnostics and infection-control experts.

[Read next: How climate change is making us sick]

The disease is still quite rare, and many doctors aren’t even aware it exists. It’s also difficult to diagnose, with the most widely used blood test missing about half of all cases, according to Ostrosky (he notes that a newer, better test is now available, though it is expensive and not widely available). In addition, the most common symptoms of infection include sepsis, fever, and low blood pressure — all of which can have any number of causes.

Infections like C. auris have also entered the public discourse thanks to the HBO series The Last of Us, the hit drama about the survivors of a fungal outbreak. An infection that can transform humans into zombies is a work of fiction, but addressing climate change that’s altering the kinds of diseases seriously threatening human health is a real-world challenge.

“I think the way to think about how global warming is putting selection pressure on microbes is to think about how many more really hot days we are experiencing,” said Casadevall of Johns Hopkins. “Each day at [100 degrees F] provides a selection event for all microbes affected — and the more days when high temperatures are experienced, the greater probability that some will adapt and survive.”

Adds Ostrosky of UTHealth Houston: “We’ve been flying under the radar for decades in mycology because fungal infections didn’t used to be frequently seen.”

* * *

Explore more from the Climate Connections series: