Grist

A company said there was only sand in the path of its new pipeline. Scientists found a thriving ecosystem.

- Feb 14, 2024, 1:30 AM

Javier Bello could scarcely believe what he was seeing in the waters off the coast of Veracruz, Mexico. Where the Canadian fossil fuel company TC Energy had claimed there was little more than mounds of sand, he saw a thriving ecosystem. Sunbeams sliced through the water, and fish danced between the delicate array of wire and black corals 328 feet below the surface. “It was incredible,” he said.

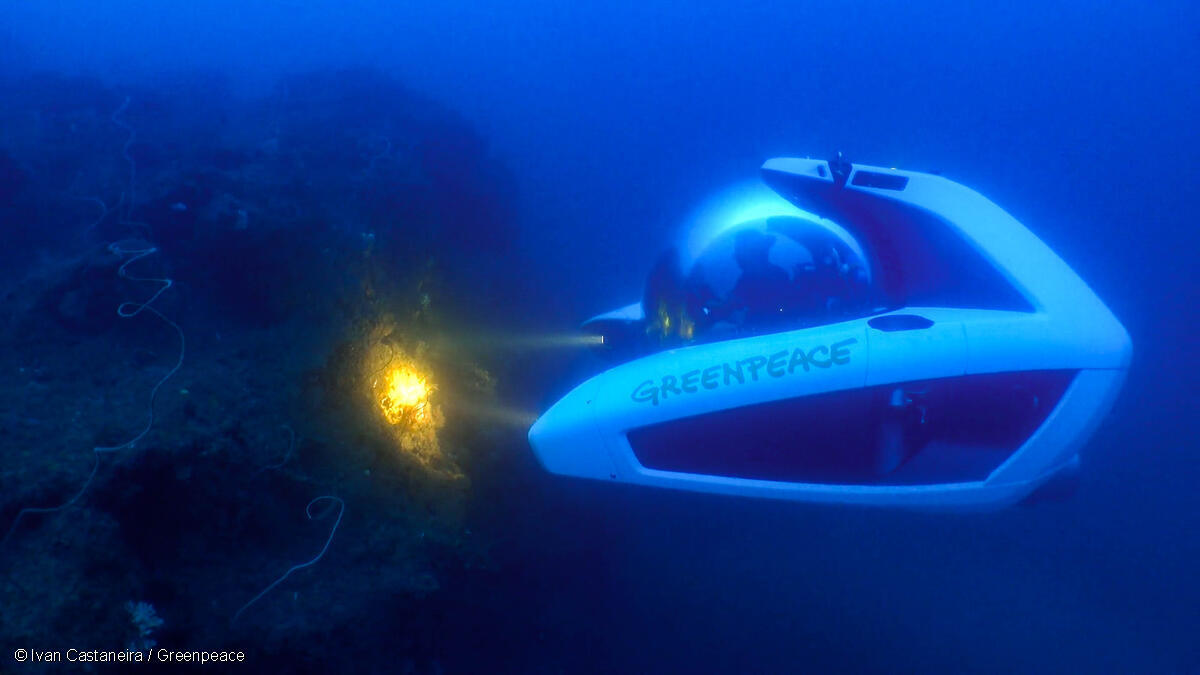

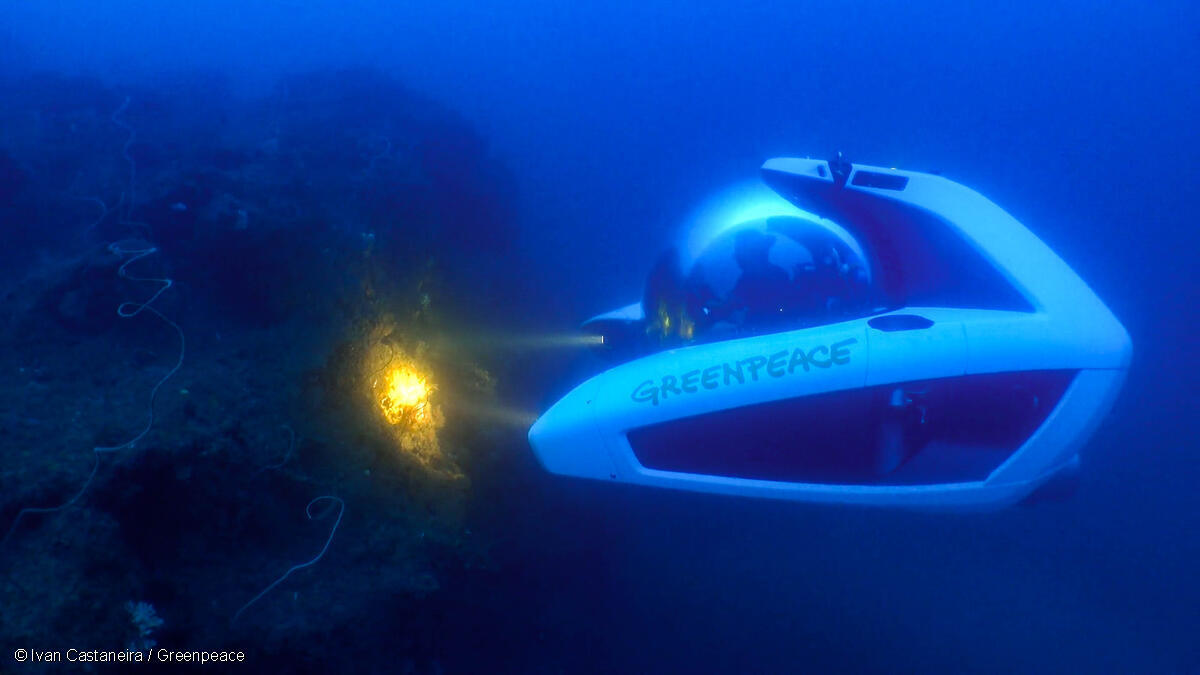

Peering from a submarine, the marine scientist was among the first to lay eyes on a marine habitat that he and others fear will be devastated by the construction of a natural gas pipeline. The whole point of the voyage, in which scientists, fishers, and activists converged aboard the Greenpeace ship Arctic Sunrise for three weeks last June, was to show what could be lost by the project.

“We don’t often have access to these kinds of research opportunities in Mexico,” Bello said, “so it is a really good example of nongovernmental organizations working with universities to make things happen together.”

TC Energy — the company behind the Keystone XL pipeline — has proposed an extension of a natural gas pipeline that would stretch roughly 497 miles from the coastal towns of Tuxpan to Coatzacoalcos in the Mexican state of Veracruz. The company has claimed that there is nothing of significance on the seafloor along its planned route, and that construction will not harm existing marine protected areas. But Bello says researchers have always had an inkling that the reefs extended beyond the protected areas.

The exact coordinates of the pipeline remain classified, but information leaked to Greenpeace by an anonymous government official pointed to a general area — about 400 feet (120 meters) from shore — which guided the Arctic Sunrise’s route. Previously, researchers had not had the resources needed to study those depths, but the glimpses by the Arctic Sunrise’s research team revealed a rich and vibrant ecosystem that extends beyond the protected areas — one that scientists like Bello would like to have the opportunity to continue to study.

But unease about the project extends beyond protecting and studying corals and fish. Pipeline opponents believe that in addition to environmental destruction, the project will disrupt the livelihoods of local communities and keep Mexico reliant upon fossil fuel, further exacerbating the effects of climate change.

In July of 2022, TC Energy announced a partnership with Mexico’s CFE, the state-owned electric utility, to build an extension to its Sur de Texas-Tuxpan Gas Pipeline. With an estimated cost of $5 billion, TC Energy announced a public offering of common shares to help fund the project the next month.

Following the investment announcements, 18 environmental organizations led by the Centro Mexicano de Derecho Ambiental warned of the pipeline’s grave risk to the surrounding coral reef corridor. They alleged that TC Energy and CFE were trying to avoid scrutiny of the project’s impact by presenting an environmental impact assessment fragmented into two pieces, one for each stage of the pipeline — terrestrial and aquatic.

“In the ocean, our main concern is that the pipeline will be built right on top of the reefs, which is very possible,” said Pablo Ramirez, a climate and energy campaigner with Greenpeace Mexico. “But even if they only build near the reefs rather than on top, the sediments could affect the reef, which is very concerning.”

Ramirez notes that Greenpeace acquired leaked documents that laid out TC Energy’s environmental review process. Of particular concern is the assessment methodology it used in determining the suitability of the proposed “dumping polygon,” where sediment dug up to make way for the pipeline will be placed. The leaked information reveals that, per TC Energy’s assessment request, Mexicos’ Safety, Energy and Environment Agency (ASEA) dropped a 50-meter rope to see what was beneath the surface and, because the rope did not reach the seafloor, concluded that the site lacked evidence of an active ecosystem.

In an email to Grist, a TC Energy spokesperson noted that “this project was specifically designed with sustainability in mind. We believe in evidence and science-based decision making. … This marine project route is one of the most studied routes ever undertaken.”

But the proximity of the proposed dumping polygon to the reef alarmed environmentalists, and when Greenpeace sought clarification, Ramirez says, TC Energy responded by providing heavily redacted paperwork, further heightening the organization’s apprehensions.

“That’s when we decided to go into the ocean and check it out for ourselves,” said Ramirez.

What they found were thriving, previously unexplored reefs — a continuation of a highly biodiverse reef system with many endemic species. Bello notes that his primary worry is the absence of transparency between the fossil fuel industry and scientists in cementing the pipeline. “There is a lack of knowledge,” he said. “They aren’t giving access to enough of the information, and during the operation of the pipeline, there could be accidents that would come with great consequences for the corals and ecosystem.”

While there is still time to stop the project, ASEA has already approved stages one and two, which account for construction on land. Through litigation and advocacy campaigns, Greenpeace and other environmental groups aim to delay the project as long as they can, hoping that Mexico’s next president will be more amenable to killing the project.

Ramirez notes that for locals, the pipeline is an infringement on their land and a threat to the livelihood of over 70,000 people whose sole income depends on fish. The threat is particularly acute for the communities of El Bosque and Las Barrancas, which could lose their fish stocks if the pipeline disrupts the marine ecosystems. At the same time, they are losing land to an advancing sea and coastal erosion, driven by reliance on fossil fuels like the natural gas the pipeline will carry. The coastlines of Mexico are heavily impacted by storms and rising sea levels — and reefs, which buffer shorelines, can help to protect coastal communities from increasingly violent storms.

Ramirez also expresses concern that the communities along the pipeline’s route haven’t been fully informed of the risks. “The companies talk to local communities about all of the so-called benefits, but when we went to the communities afterward and presented that the projects are to transport methane, which can be explosive, the locals were very shocked.”

“We didn’t even know about the pipeline production,” Lupe Cobos, a resident of El Bosque, told Grist. “And in a community that is facing major effects of climate change — we are literally losing our homes — that is important information.”

Since Greenpeace representatives have begun speaking with Veracruz locals about the potential risks, Ramirez says, the community has become keen on the organization’s efforts. But in this area, resistance to development can be dangerous. Although Greenpeace has not had reports of anything untoward regarding this pipeline, the risk is still foremost in the minds of locals.

“There is a lot of violence and repression for this kind of resistance,” Ramirez continues, “so we’re still trying to figure out the best way to do it, and how Greenpeace can assume the risk.”

Veracruz is no stranger to the oil industry. Promises of development and benefits from oil have been pledged to locals for more than a century — and yet more than 60 percent of Mexican households live in energy poverty due to accessibility, affordability, or both. According to Ramirez, Greenpeace has heard anonymous reports from residents that TC Energy has already approached fishing communities in the state of Tabasco, offering them money in exchange for their assurance not to oppose the project. (TC Energy did not respond to Grist’s emailed question about the allegation.)

“We have to fight this narrative that they actually want to help the communities,” Ramirez said. “Because at the end of the day, this kind of energy model is leaving the communities behind.” He believes shifting to renewables would be a better strategy to promote energy security and independence for Mexico.

He notes the effects of the 2021 Texas winter freeze, when Mexico lost its gas supply due to frozen pipelines in the U.S. When the states were forced to prioritize national consumption, around 5 million people in Mexico lost power; although most of the affected customers had their power restored within the day, even more people were then affected by temporary planned outages as the National Energy Control Center struggled to maintain a reliable supply.

Additionally, the new infrastructure would go against the international goal of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, as set forth in the Paris agreement. At COP28, the annual U.N. climate conference at the end of last year, countries — including Mexico — participated in the first “global stocktake,” assessing progress toward the Paris Agreement goals. The resulting agreement named fossil fuels as the driver of climate change for the first time, and called on countries to begin “transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems.”

“The fossil fuel model does not fulfill Mexico’s needs,” said Ramirez. “Increasing our gas consumption means that we will remain dependent on U.S. and Canadian gas. We need to change the focus of the model where the betterment of the people is front and center of energy policy.”